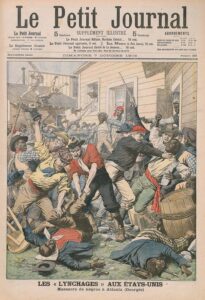

Violence has long been used to control and intimidate minority groups in the United States. This hostility has targeted at a wide array of nonwhite people: Native Americans, Asians, Mexicans and especially African Americans. The mold was set during slavery when slaveholders resorted to physical coercion to enforce human bondage. After the Civil War, with the founding of the Ku Klux Klan, vigilantism served the same purpose of maintaining the old racial hierarchy. From the 1870s to the 1950s, an estimated 4,400 African Americans were lynched without a trial, mostly in the states of the former Confederacy. During the same decades, mob violence rained down on scores of Black communities in the South and elsewhere. The causes varied, from political coups in Louisiana and North Carolina to conflicts over segregation in Illinois and Texas to hysteria over crime in Georgia and Oklahoma to economic competition in Arkansas and Pennsylvania. Whatever the spark, these acts of racial terror killed hundreds of African Americans and destroyed millions of dollars‘ worth of residential and commercial property.

Violence has long been used to control and intimidate minority groups in the United States. This hostility has targeted at a wide array of nonwhite people: Native Americans, Asians, Mexicans and especially African Americans. The mold was set during slavery when slaveholders resorted to physical coercion to enforce human bondage. After the Civil War, with the founding of the Ku Klux Klan, vigilantism served the same purpose of maintaining the old racial hierarchy. From the 1870s to the 1950s, an estimated 4,400 African Americans were lynched without a trial, mostly in the states of the former Confederacy. During the same decades, mob violence rained down on scores of Black communities in the South and elsewhere. The causes varied, from political coups in Louisiana and North Carolina to conflicts over segregation in Illinois and Texas to hysteria over crime in Georgia and Oklahoma to economic competition in Arkansas and Pennsylvania. Whatever the spark, these acts of racial terror killed hundreds of African Americans and destroyed millions of dollars‘ worth of residential and commercial property.

The tensions that led to the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre had a familiar source. For weeks, the city’s four daily newspapers ran irresponsible and unfounded stories about African American men assaulting white women. On the evening of Saturday, Sept. 22, the city ignited as white mobs downtown attacked and murdered Black people at random. At least a dozen people died that night, but the horror wasn’t over. The bloodshed widened over the next three days as the police and vigilantes invaded Black neighborhoods to disarm residents who wanted to defend themselves. At least another dozen people died, leaving scars that would linger for decades. Follow this link for an explanation of why an event that was known for a century as a riot is now more accurately called a massacre.

+ 1865

The Civil War ends, bringing emancipation to more than 400,000 formally enslaved African Americans in Georgia.

+ 1877

The last U.S. occupying forces leave the state, closing the Reconstruction era of racial reforms. White leaders quickly re-assert political control.

+ 1891

The Georgia legislature passes a law allowing cities to separate streetcar riders by race, one of a growing number of efforts to enforce segregation.

+ 1899

A mob in Newnan, Ga., lynches Sam Hose for allegedly killing a farmer. Four days later, another man is lynched for speaking out about the Hose lynching. Both incidents are part of a rise of racially motivated murders at the turn of the 20th century.

+ April 1906

Hoke Smith and Clark Howell wage a bitter campaign for the gubernatorial primary in which the hottest issue is passing laws to keep African Americans from voting.

+ September 1906

Atlanta’s four daily newspapers run a series of unfounded stories about Black men assaulting white women, whipping up an atmosphere of fear and hyper vigilance.

+ Saturday, Sept. 22, 1906

Newspapers issue multiple extra editions with lurid headlines about the latest alleged assaults. In downtown Atlanta, more than 10,000 people are gathered, and the mood grows tense.

9:30 p.m.: Mobs attack a Black bicycle messenger near Five Points. Violence rages out of control. Gangs pull people off streetcars and beat them to death. They attack Black-owned barbershops and shoot one employee dead. They stab a man and throw his body off a viaduct. They mutilate bodies and drag them to the foot of the Henry Grady statue on Marietta Street. In 2½ hours, at least a dozen African Americans are killed.

12:00a.m.: The state militia is called out, and the violence dies down as troops arrive and heavy rainfall moves in.

+ Sunday, Sept. 23

White vigilante groups fan out through the city looking for African Americans who are rumored to be arming themselves in self-defense. In the southern suburb of East Point, a lawman arrests Zeb Long on suspicion of possessing guns, and a mob lynches him.

+ Monday, Sept. 24

A posse of police and civilians invades the south Atlanta community of Brownsville to disarm Blacks. A gun fight breaks out and at least three people die, including a white police officer and a 70-year-old Black veteran of the Union army. Two men arrested that evening try to escape police custody and are shot to death.

+ Tuesday, Sept. 25

Two more African American men are killed by police in a gun battle in the Fourth Ward on the east side.

+ Wednesday, Sept. 26

White and African American leaders convene — the first interracial meeting of its kind in Atlanta — and discuss ways to avert racial violence. White officials blame lawless Blacks and low-class whites for the bloodshed.

+ Friday, Sept. 28

Max Barber, editor of the Voice of the Negro, flees Atlanta after the police commissioner threatened him with jail and hard time on a Georgia chain gang. His offense? He sent a letter to a New York newspaper disputing an earlier letter claiming that Black rapists were the reason for the massacre.

+ December 1906

The city’s official report places the number of people killed in the massacre at 12, but historians later conclude that at least 25 died. The massacre traumatized Atlanta’s Black community; reinforced segregation in the city; and hastened a more activist approach to civil rights, leading to the founding of the NAACP in 1909.

Official sources at the time placed the death toll at a dozen, but historians agree that at least 25 people died during four days of racial violence in on Sept. 22-25, 1906. Here are the names of 20 known victims. There were reports of other fatalities, but their names are unrecorded. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, lists 11 victims of the massacre as unknown, all of whom perished on the first night.

Wiley Brooks, 30, occupation unknown, was arrested during a police raid in the Brownsville neighborhood on Monday evening, the third day of violence. He was being taken by streetcar to the jail downtown when vigilantes attacked him. He tried to run away and was shot to death.

Milton Brown, 22, a driver for a coal company, was attacked on Saturday, the first night of the massacre, by a mob that had broken into a hardware store on Peters Street to steal weapons. Suffering from multiple knife and gunshot wounds, he lived long enough to give an account of what happened. He left a wife and two children.

Walter Brown, age and occupation unknown, was reported as a fatality by The Atlanta Constitution. The newspaper said he was assaulted by a mob downtown on Saturday night.

Marshall Carter, 13, died of induced asphyxia and a battered skull suffered on Saturday night. The Atlanta Journal first reported that he was injured by other African American children, but it later listed him among the people who died in the massacre. One book about the massacre, Negrophobia, also lists him among the fatalities.

Frank Fambro, 38, a grocer, was shot to death on Monday evening while standing in the front doorway of his home in Brownsville. Some witnesses said he had been involved in a gunfire exchange with county police. He left a wife and a child.

Stinson Ferguson, 25, was found shot to death in the abdomen on Saturday night downtown. He was unmarried and listed no occupation. He was buried at South-View Cemetery.

James Fletcher, 17, a student, was shot to death by police early Tuesday morning, the final day of the massacre. Police had been summoned by reports of rioting in the Fourth Ward and said that once there, they came under fire from a house at the corner of Randolph and Magruder streets. They claimed that two young men started firing at them, and they pursued and killed them.

James Heard, 30, a Fulton County police officer, was part of a posse of lawmen and vigilantes who marched into the Brownsville neighborhood on Monday evening in an effort to disarm Black residents. Gunfire broke out, and he was struck in the head on Jonesboro Road. One of two known white fatalities in the violence, Heard had been married less than a year. Authorities arrested more than 200 Brownsville residents in the aftermath of his killing.

Zeb Long, 38, a laborer, was arrested in East Point on Sunday night, the second day of the massacre. Police said they suspected him of carrying weapons and found a revolver and ammunition in his possession. They him up in a flimsy holding shed to await transport to the county jail in Atlanta. Some time overnight, a mob removed him from the calaboose and strung him up from a tree.

Leola Maddox, 30, a janitor, was attacked by the mob on Saturday night as she walked with her husband on Mitchell Street downtown. Stabbed and beaten, she lingered for a week before dying of her wounds.

Sam McGruder, 30, a brickmason, was arrested during the Monday evening police raid in Brownsville. He was being taken to a jail downtown when vigilantes tried to seize him. He ran and was riddled in bullets. He owned a home in south Atlanta and had a wife and family.

Will Marion, age unknown, was a young man who worked at Leland’s Barber Shop on Peachtree Street as a bootblack, an old-fashioned term for someone who shined shoes. He became one of the massacre’s first victims when violence broke out Saturday night and members of the mob burst into the shop and shot him in the head as he was bent over a customer’s shoes. Barbers looked on in shock as he died.

Will Moreland, age unknown, a porter, was one of two young men killed by police in the Fourth Ward early Tuesday morning. Police accused them of being snipers and engaged in a fierce gun battle with the two.

Clem Rhodes, 24, a laborer, was shot to death on Saturday night on Butler Street, in downtown Atlanta. A native of Crawfordville, Ga., he left a mother, a wife and four children.

Annie Shepard, 15, a maid, was shot in the chest on Saturday night in front of her family’s home northwest of downtown Atlanta. Some newspaper reports said that she died in a drunken brawl among Black neighbors, but other sources said that she was shot by an unknown white man.

Frank Smith, 18, a Western Union telegraph messenger, was attacked on Saturday night as he tried to outrun a mob on the Forsyth Street viaduct downtown. He was stabbed in the chest and his body thrown off the bridge. A well-liked resident of Summer Hill, he was said to be the sole support of his mother. Authorities charged a white man with his killing but were unable to secure a conviction.

Mrs. Robert C. Thompson, 33, dropped dead of a heart attack after she witnessed the murder of two African American men on Monday evening. According to multiple sources, she was outside her home on Crew Street when a mob attacked the two men, who had been arrested in the gun battle earlier that night in Brownsville. Mrs. Thompson, a wife and mother of two, was one of two white people known to have died as a result of the violence.

William Henry Welch, 30, occupation unknown ducked into a pool room on Peachtree Street to evade the mob on Saturday night. Men followed him inside, and one of them shot him down. The assailant ran out of the shop and disappeared into the crowd. Some sources spell his name Welsh.

John White, age and occupation unknown, was found dead downtown after the Saturday night violence, according to The Atlanta Journal.

George Wilder, 70, was the oldest known fatality in the massacre. Once enslaved in middle Georgia, he ran away to join the Union Army during the Civil War. When a posse of police and vigilantes invaded the Brownsville neighborhood on Monday evening, the disabled veteran got his old-fashioned muzzle-loaded rifle and confronted them. He was shot dead. His marker at South-View Cemetery reads: “A soldier of the Civil War/was killed in the riot.”

For more than a century, the racial violence that wracked downtown Atlanta in 1906 was usually referred to by historians and journalists as a riot. But that terminology did not give an accurate picture of what happened. Now it’s finally changing. The National Center for Civil and Human Rights, in partnership with the Fulton County Remembrance Coalition, launched a campaign in 2022 to change the name of the event to a more accurate term, massacre. Media outlets and state education and humanities officials were approached about the reasons (for a fuller explanation, see this letter). Historians of 1906 were lobbied. A petition calling for the change was started on the Center’s website.

The campaign yielded quick results. The George Department of Education changed its curriculum to reflect the updated terminology. Georgia Humanities and the editors of the New Georgia Encyclopedia changed references in that comprehensive online reference work. Media from radio station WABE to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution decided to go with the updated wording. There’s still more work to be done on the national level with Library of Congress classifications and other media.

The name change follows a trend to relabel the racial conflagrations of the late 1800s and early 1900s, which were essentially broad attacks on black communities, not riots. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and the 1898 Wilmington Coup are among the onetime “riots” that have been renamed to better document their true history. Now the Atlanta tragedy of 1906 is joining them.