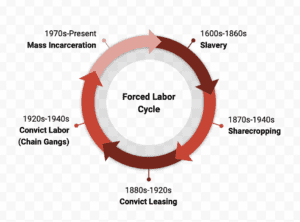

At the end of the Civil War, the Southern economy was in shambles and cities that thrived by producing and transporting goods to serve the slave economy struggled to reinvent themselves. Though the 13th Amendment promised to end the practice of relegating human beings to the status of property, it made an exception by allowing involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. Therefore, government leaders and private businesses colluded to re-enslave black men, women, and even children by falsely convicting them of crimes and sentencing them to labor.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Southern states arrested thousands of Black Americans for petty or false crimes and leased them to private companies who forced them to work in harsh and deadly conditions. This practice became an industry unto itself with prison labor camps and convict leasing programs reinstating bondage for generations after the war ended. Historian Douglas A. Blackmon refers to convict labor as “Slavery by Another Name.” While most states ended convict leasing in the early 20th century, similar abuses continued for years in the form of chain gangs and evolved into the involuntary prison industrial complex – creating our current carceral system.

The period of Racial Reconstruction in the U.S. marked the rise of the convict leasing system in Georgia, particularly within the railroad industry. The exploitation of forced labor and leases to private companies allowed the state to advance its railway systems to increase trade and bolstered the economic structure of the state. Governor Rufus Bullock of Georgia was instrumental in the management of this new system that some argue “rivaled slavery itself”.

At the end of the Civil War, William Sherman made his famous march to the sea, scorching much of Atlanta to prevent the Confederate forces from utilizing the city after they abandoned it. Atlanta – perhaps more than any other major city of the South – needed a significant rebuilding. Therefore, after the war, Atlanta was the site of several industries that heavily relied on forced labor, including convict leasing, convict labor, and prison farms. A few miles to the northwest of the Center, two industrial complexes — the Chattahoochee Brick Company and the Bellwood Quarry — were notorious sites of forced labor in Atlanta.

The businesses at Bellwood Quarry and the Chattahoochee Brick Company in Atlanta relied on this abusive practice. At both sites, African American prisoners labored under conditions documented as “horrific,” with starvation and sleep deprivation. Physical abuse and death were common. Both enterprises played a crucial role in providing building materials for the reconstruction of Atlanta after the devastation of the Civil War. The City of Atlanta now owns both sites.

Chattahoochee Brick Company

The most prominent site was the Chattahoochee Brick Co., in northwest Atlanta on the Chattahoochee River, owned by former Atlanta mayor and police commissioner, James English. From the 1870s until the early 1900s, the company leased thousands of convicts to produce bricks from red clay along the riverbank. Hundreds of laborers were subjected to inhuman conditions and unspeakable treatment, including whippings and disablement. At its height, those re-enslaved produced approximately 300,000 bricks every day for the Chattahoochee Brick Company.

Chattahoochee Brick’s production severely declined after the legal outlaw of convict leasing in 1908, although the company continued its operations until 1978. The City of Atlanta has since purchased the Chattahoochee Brick site with plans to create a green space that will honor its history and shed light on the experiences of the men and women who toiled there. You can find more information on our collaboration with the City of Atlanta here.

Bellwood Quarry

At the same time, convicts were subjected to grueling conditions and physically demanding labor at the Bellwood Quarry, also in northwest Atlanta, where they extracted and crushed granite. Bellwood Quarry is now the centerpiece of major infrastructure projects in and around Westside Park, which connects to the Beltline’s Westside Trail. Neighborhoods adjacent to the Beltline corridor are predominantly Black and lower-income and experiencing “high pressure for gentrification” in a city that persistently ranks among the most inequitable in the United States.

The Truth and Transformation Program is organizing an equity-focused, multi-stakeholder engagement effort to build a memorial about convict leasing at Atlanta’s newest and largest public green space, Westside Reservoir Park. Our goal is to create a collaboration across sectors that demands equity and mutual respect to create transformation.

The forced labor system (and racial terror) in the post-Reconstruction era were inter-connected actions towards the goal of subjugating African Americans to a place of inferiority and claiming an entitlement to their labor for economic and political gain. Affected Black families suffered untold pain of separation from loved ones and severe economic insecurity due to generations receiving little to no pay for their work – contributing to the now largest racial wealth gap in the country. Today, many of the areas of forced labor in Georgia have suffered devastating effects of economic divestment, while the descendants of convict leasers have assumed mass amounts of wealth from their practices. Some of the largest companies in Georgia directly benefited from or derived their initial capital from forced labor earnings. From a federal lens, studies have shown that the convict labor system has contributed to higher unemployment, lower participation in the labor force and slower growth of manufacturing wages.

In the fall of 2019, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights decided it was time to uncover and acknowledge the stories of racial terror hidden deep within the history of Atlanta. To help support this work, the Center applied for a grant through the Arthur M. Blank Foundation, a major funder of the development of the west side of Atlanta. In this collaboration with the Foundation, The Center was charged with conceptualizing a meaningful yet narrative memorial on two sites of convict leasing and labor—the Bellwood Quarry and the Chattahoochee Brick Company. Not only would this work be the first of its kind within the city of Atlanta and for the deep South more broadly, but there were other major players in the city with an invested interest in its development. There were also individuals and organizations, working tirelessly towards these efforts, often for free, who needed a seat at the table. There was a need to connect, engage in fruitful dialogue, and create community and the Blank Foundation graciously offered to host this retreat at West Creek Ranch in Montana.

In the summer of 2021, before the convening, the West Creek group documented procedures on how this group would function and interact. This document would eventually lead to the Charter that governs the group today. The process of gathering community leaders, corporations, city and local officials, and even the descendants of those who were victimized years ago throughout the state demanded inclusivity and intention. Every impacted voice deserved representation and the groundwork had been set. The relationships that were built during the West Creek Ranch retreat continued through countless meetings and conversations, which, ultimately, led to a core group of individuals dedicated to the inclusive advancement of Atlanta’s west side—The Westside Atlanta Stakeholder Group. The group is comprised of community activists to represent the affected; scholars to inform the work; government officials to put word into action; and corporations to gain a greater understanding of the communities their expansive efforts displace and uproot.

As a steward of the group, the Center remains dedicated to understanding how to grow and engage the group, support the personal and professional work of the members, and use their expertise to advance advocacy efforts better and more effectively. The relationship between the Center and the Westside Atlanta Stakeholder Group has been mutually beneficial. Since its inception, the group was responsible for successfully advising the Center in securing its grant to the Mellon Foundation and assisted in selecting the community engagement firm tasked with informing and engaging residents of the west side around memorial efforts. In turn, the Center has established a microgrant fund to support the efforts of the stakeholders who volunteer their time and energy to this cause. Also, the Center is collaborating with the City of Atlanta to memorialize the Chattahoochee Brick site, by partnering on community engagement efforts to foster discussions and awareness of the history of the site. There is much to do to honor the victims of forced labor in the city, but the Westside Atlanta Stakeholder Group will be instrumental in leading the charge.

Words can have a profound impact on our understanding of hidden or erased history. Check out our Truth & Transformation Glossary to learn more key terms, dates and individuals related to forced labor, both in Atlanta and the United States.